On Friday, my Sex on Screens class attended the Tri-College Symposium of Women of Color in Academia, a 5 hour event titled “Intimate Subjects: Gender and Race in Theory and Practice.” The speakers were Celine Parreñas Shimizu of San Francisco State University, Rhacel Salazar Parreñas of the University of Southern California, and Juno Salazar Parreñas of Ohio State University. The three women are sisters whose work in film and gender/sexuality studies, sociology, and anthropology share themes of interrogating perceptions of gendered and racialized subjects, especially Asian women. As Celine cheerfully noted before her presentation, the sisters had never before presented together, so this event was as exciting for them as it was for us. Each presenter was introduced by a representative from Swarthmore, Haverford, and Bryn Mawr, and each of the local professors noted that they shared a personal connection with the sister they were introducing. My classmates and I were especially amused when Professor Hoang Tan Nguyen–who teaches our course–revealed his connection to Juno. They’d been introduced at a queer youth group in San Fransisco, and he joked that they’d “gone from being angsty queer teens to jaded queer professors,” a humorous attitude that was reflected throughout the symposium even as the presenters covered rather serious topics.

The first presentation was Celine Shimizu’s “Claiming Bruce Lee’s Sex: Memoirs of the Wholesome Wife, Memories of the Salubrious Mistress,” a riveting dissection of two conflicting memoirs of Bruce Lee published by his wife and his mistress after he died. If anyone had asked me anything about the end of Bruce Lee’s life before the symposium, I would’ve shrugged and tried to pretend I already knew he was dead (yeah, I know, embarrassing). I had no idea that his death had been an international sex scandal–he died in his mistresses bed! Shimizu talked about the ways the wife and the mistress tried to claim Bruce Lee through their romantic and sexual relationships with him. His wife’s memoir paints him as unknowable to outsiders, relishes in the sanctity of their marriage while addressing the tensions of being an interracial couple in the 60s, and asserts his manhood through his role as a husband and a father. Her Bruce Lee was exceptional to his race, a lingering example of the sole case of a publicly validated Asian manhood. The mistress’s sexually explicit film portrays a ferocious lover, a deep bond created by the sanctity of intraracial relations, and a rollicking drug-infused passion that ruled his final days. She sets her claim on Bruce Lee by depicting their love as uncontrollable desire legitimized not by an institution but by their shared ethnicity. But Shimizu refused to condemn either woman or choose one version as the truth–instead, she turned the entire discussion on its head by recontextualizing the works as acts of grieving. She also shared how she had come to this, explaining that after the sudden death of her youngest son, she’d experienced a radical transformation in her conception of self. The wife and the mistress were not just trying to claim Bruce Lee, they were trying to reaffirm their own senses of self in the wake of the loss of the man their identities had been tied to. This personal noted reinforced the theme of intimacy that was so crucial to the symposium.

Rhacel Parreñas followed with “Mobilizing Morality: The Labor Conditions of Migrant Domestic Workers in Dubai” in which she complicated the narrative presented by organizations such as Human Rights Watch to explore the ways in which migrant domestic workers in Dubai exert their agency. This sociological presentation was a bit more heady than the first, but it was fascinating to see how Rhacel broke down the statistics to show how a recent Human Rights Watch report that used her interviewees got it all wrong. When most people think of migrant domestic workers in Dubai, they probably think of the horror stories: starvation, women being locked inside homes, and the many circumstances that force Filipina workers to migrate internationally to care for other people’s children so that they can afford to raise their children who are left behind in the Philippines. While there’s no way to deny the tragedy of the latter, Rhacel was mostly talking about how domestic workers are actually treated relatively well on the whole and why this is true. The Philippine government–specifically the Office of Placement and Protection–runs training seminars for migrants in which they are taught their rights and how to get them in the face of a lack of legislation. The women are instructed to appeal to their employer’s morals, because when employers treat their employees well, the employers get the satisfaction of feeling morally superior to their neighbors. They’ve also been instructed about where to go, when they have to get there, and what to say in situations of abuse. When organizations like HRW try an overall condemnation of actions in the hopes of shaming people into better behavior or creating laws, it often backfires. Emiratis denounced HRW as Orientalist and Islamophobic while non-Emirati residents of Dubai dismissed the reports as not pertaining to them since it is common knowledge that abuse is almost solely perpetuated by older, rural people who were alive when slavery was still legal in the UAE. It’s simply not as effective as the tactics used by migrant workers to mobilize the morals of their employers. Rhacel clarified that she was not trying to overlook the abuses or the tragic nature of the economic situation that forces migration, but that she was trying to present the facts so that people who try to help don’t end up doing more harm than good.

At this point there was a much-needed coffee (and more importantly, snack) break before the symposium continued with Juno Parreñas’s presentation titled “Life After Extinction in the Wild: Orangutan-Human Futures of Interdependency in Malaysian Borneo.” Her presentation on her anthropological fieldwork at an orangutan rehabilitation center focused on ideas of freedom and autonomy and how there are parallels between human struggles for decolonization and the plight of orangutans. Juno’s blend of cultural and biological anthropology fascinated me, as did her oh-so-casual references to anthropologists she’d worked with whose books I’d read in my classes. I was also pretty starstruck by her snazzy red velvet blazer. Her talk was definitely heavily within the theoretical realm as she discussed the possibility of extending the notion of decolonization to the natural world. One of her main points was that interdependency can be both mutual and unequal–for example, orangutans need the caretakers for survival, and the caretakers need the orangutans to draw economic resources for survival, but only one group is confined to the reservation. Also, the man who runs the volunteer tourism group needs the labor of the indigenous woman who takes care of the baby orangutans, and she needs him for her economic survival, but because her English is weak she cannot ask him to raise her pay to a living wage. In these examples it’s clear how Juno’s talk related to the overarching themes of gender and race, and her descriptions of the interactions with the orangutans challenged my conception of the word intimacy.

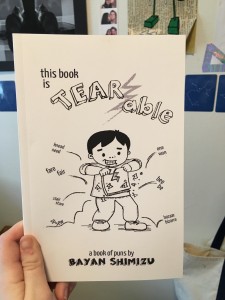

The presentations were followed by a roundtable which invited audience questions. The sisters had even organized prizes for the first 10 questions–signed copies of Celine’s 13-year-old son Bayan’s book, This Book is Tear-able! While the questions and answers were certainly interesting, funny, touching, and enlightening (there’s really nothing like watching three women interact as academics and as sisters), I was way slightly more excited by receiving a copy of the book. Bayan, his mother, and his aunt had all signed it, and he’d even included a little note: “enjoy!” It is a book of puns. I’d kind of expected to make a joke about sitting in Carpenter for 5 hours to receive a book written by a child, but the introduction caught me off guard with its intense thoughtfulness and heart-wrenchingly precious honesty.

The book is dedicated to his little brother, who died suddenly two years ago due to an infection. Bayan’s introduction describes his death, the trip to the hospital, the realization, and the overwhelming depression he experienced in the wake of losing his brother. It also describes how he started collected puns from his friends and friends of his brother as a way to relive a connection they’d shared and explore joy in the face of loss. The introduction displays a powerful awareness that underscores the cute, cheesy humor of the short book–his second published volume of puns. The symposium as a whole was an incredible experience that continued to resonate with me days after it happened because of the way the sisters invited the audience into their work and their lives. It seemed clear to me that Bayan is on a path to follow his family’s footsteps and delve ever deeper into humanity’s many intimacies.